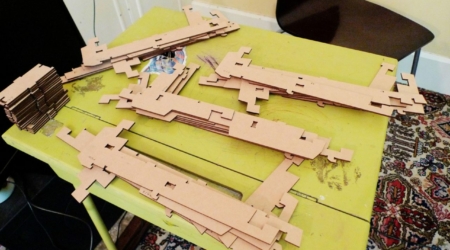

We keep a selection of the most popular materials on site in order to speed up your production time. However, we are happy to source materials we don’t keep for you, or laser cut any materials you provide. Just let us know which material you are planning to cut and we will advise you on tolerances and cut quality before we start.